This paper explores five levels of accessibility, extending the familiar notion of wheelchair access to the sensory and cognitive levels of accessibility. It is slanted towards autism-related accessibility, but the framework could be generalized and adapted to other kinds of people. The levels to be described are:

- movement

- sense

- architecture

- communication

- agency

Basically, I am looking at what makes the difference between a place or event that a lot of different kinds of people can go to and get what they need effectively, versus one that is impossible to get to, threatening, confusing, or in other ways unavailable. Autistic people avoid lots of kinds of places for a variety of reasons, but using this accessibility framework, I hope to make it easier to talk about specifically why they avoid those places, by giving vocabulary to why those places are not accessible, and to make it easier to make those places accessible.

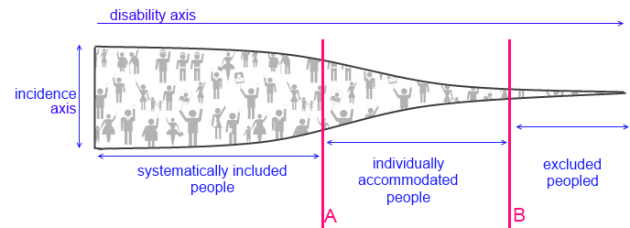

Before I get into the levels, I need to define some abstract things, starting with this graphic explanation of inclusion versus accommodation.

Inclusion

This chart shows a bunch of people clustered on the left (without a disability), and progressively fewer people who are more disabled or at least more divergent. The three categories are those who are systematically included (the largest group; the one the system was made for), the group that is not included by design but can be individually accommodated by some adaptation, and those who are excluded.

For the math people out there, this is half a bell curve showing incidence (Y) over extent of disability (X) with a reflection across the X axis, showing two of the deviation lines A and B (not necessarily the first two standard deviations but maybe – some sociomathemetician could possibly comment on this).

In this picture, you can imagine moving the A line left or right, which would throw some people into a different category. The aim of deep accessibility is to move the A line right, so more people are systematically included, and will not need accommodations. (They can come as they are.) The effort to push line A to the right has to go against social forces that want to move it to the left. The demands of capitalism require the people between A and B to be an ever larger pool of people, as this essay explains, so there is a very strong economic force moving A to the left. Another effectively left-pushing force comes from medical advances: there are more people surviving who are in the A-B range.

The B line can also be moved left of right. Pushing it right means finding adaptations (like glasses or communication devices) that allow someone who otherwise would be excluded to be accommodated with that adaptation. Where the B line falls represents the customer base of the therapy industry (and other elements of the larger medical industry) because they make money from modifying people. Their incentive is for the pool of people to the right of B to be as large as possible; they benefit more from slow individual accommodations than from mass produced systematic accommodations or systematic inclusion.

The take home point here is that although some people can be changed a little, the major changes in accessibility come from changing systems – where the A and B lines fall – so we should be thinking about how to move the lines, not only about how to fix people. And that is why I’m focusing on changing spaces.

A problem with looking at individual disability is that people are in complex systems and isolating out one so-called disability is likely to be impossible or a wrong guess. For example if a person gets anxious in a certain space, you could say they have an anxiety disorder or autism, but so what? Applying the framework of deep accessibility to the space itself, rather than focusing on fixing people avoids the nearly impossible task of understanding the complex causes of the response in that one person, and you would be helping a lot more people.

Accessible space

When I talk about “space” or “places”, I mean it in a broad way like some architects use it, to include the full experience of physical space and the way it is managed. It can be a temporary event, not necessarily tied to one physical space.

There is a design philosophy known as permaculture, which is an approach for ones own habitat, with a presumption that a person can shape their own place to suit them. What I’m doing here is a design approach in that same way, but applied to public space as opposed to habitat. That kind of space has to fit everyone, not just the one occupant, so it needs a different set of design rules.

The main guideline for knowing if a space is accessible is that people don’t feel assaulted there; they feel safe and their needs are being met. The measure is by what the users of the space say themselves, not what observers say.

The endpoint of the theory here is that if we make a space accessible, the bad things about disability can evaporate; the presence of a disability becomes neutral differences. The thing that makes differences disabling is more a mismatch with environment than it is a problem inherent in a person. Disability is still an un-erasable fact – some people cannot do some things or are very bad at them – but with deep accessibility, the system can include more of us more of the time.

The concept of “autistic space” is a variant of “safe space” where people can be themselves more fully. When it is working well, a magic fills the air because an autistic person feels at home there, not disabled, not under any kind of assault. It seems to happen only when autistic people are in charge of the space and are the majority; otherwise the other kinds of people tend to squash that magic. But what if we define autistic space as space that is deeply accessible and make the requirements more explicit? Would non-autistic people then be able to help create that space and preserve it, and would it be more inclusive?

The 5 levels of accessibility

Movement – getting there

At the movement level, the question is about physically getting there and moving around. A space is accessible on this level when the person can get everywhere, and reach and see things.

This level is mainly what the Americans with Disabilities Act is about, and there are design standards (mainstream, already in practice) governing hall width, ramps, doorways, handles, writing surfaces, and other things that make it possible for people who use wheelchairs and walkers to get around. Despite the focus on wheelchairs, this level also pertains to children, unusually short, tall, or wide people, people who have or use only one hand, and those less fine motor control. There is a lot written about this level so I won’t say any more about it.

Sense – being there

At the sense level, the question is about “being there”. The space is accessible when the person can be there in a present state of mind and can distinguish relevant things from noise, without sensory overload. The design points to consider at this level are lights, sounds, textures, scents, vibrations, and toxins.

Some people have a narrower range of tolerance for these things than others, so to be accessible, here’s a partial list of things to avoid: fluorescent lights, too much or too little light, loud noises, perfumes, and vinyl floors and carpets.

It can be thought of like food allergies – some people are “allergic” to fluorescent lights, so they can’t be forced on everyone using the space.

Also the patterns in each of the senses are important. Bright lights may be OK but flashing lights may induce seizures or discomfort. Sudden sounds are more overloading than gradually increasing or expected sounds. Carpets with complex color patterns may be overstimulating, not from the color itself but from the size of the dots.

There is no way to specify a level of “too much” light or sound, as each person’s tolerance is different. So the less sensory overloading factors there are, the more accessible the space is.

People don’t always know what the source of over-stimulation is, or even that they are experiencing sensory overload. They may get irritable and blame it on something else.

Architecture – orienting

At the architecture level, the question is about the emotional state of the person in relation to the function of the space, or the question of how the space leads people into its function. Architects design entryways, libraries and airports very differently because the functions are different – not just according to the main function of the facility, but in many detailed ways.

A space is accessible at this level when the person can organize the space into its functions, can orient their movements, and can escape. A user of the space would know, for example: “I’m in the public area, and I can leave at any time. There is a bathroom I can use. After I go through those doors, I’ll be seen by the person in charge, then I’ll have to wait to be let go, at which point I’ll come back in here again.” They would know that just by looking and feeling the space, without reading or any language (which is covered in another level). Other mammals are alert to this level of accessibility: think of cats or deer and how they behave when they don’t know the escape route or are disoriented – they can get scared or aggressive. Like those animals, people rely on non-linguistic cues to orient and those cues affect our emotional state.

The architectural accessibility design points include:

- Size of spaces in relation to each other. For example, an old architectural rule of thumb is that a main entryway is large and leads into the largest room, and successively smaller doors lead into successively smaller rooms. It feels backwards and disorienting when a small door leads into a large room; it can interfere with mentally mapping the space.

- Colors. For example, white door trim against a dark wall marks that door as the invitation. Colors can also indicate a usage pattern – such as orange things are off limits to the public.

- Glass. Windows provide safety in public spaces, and allows for orienting to the outside.

- Flow of people. Carpets, painted lines, or other patterns can help specify the intended flow of people in a space.

- Edges. Like deer who often walk along the edge of a meadow, people prefer the safety of edges over walking straight through the middle of a large space.

- Public versus private indicators.

- Exit directions.

- Heights. Vertical distance feels dangerous even if there is no real danger of falling.

The kinds of people who may most value this kind of architectural accessibility include those with past traumas or other feelings that are aroused when they feel confused or trapped, and also those with cognitive or communication styles that don’t rely on language as much as usual – for them in particular, natural or non-language cues can be important to feeling safe and understanding.

Communication

At the communication level, the question is whether the person can understand and make themselves understood in the space. Beyond the choice of language (English, American Sign Language, etc), there is a tree of knowledge about the space that has its own terms and structure, and that knowledge tree needs to make its way into the user’s mind. The knowledge tree can also be called an organizational scheme. A space is accessible when the person can communicate in both directions using the terms of that scheme, and can function equally.

For example, there is a scheme for using a library, that most people know only because they have been taught it explicitly: you browse for as long as you want; you are allowed to read books in the library without checking them out; you are not supposed to re-shelve them yourself; and so on. An accessible library might prominently explain that scheme and not just expect people to know. People who are autistic can often miss the scheme for spaces such as entertainment venues, hospitals, or other places with a fairly complex set of expectations. The act of ordering an item in an unfamiliar eating establishment, for example, can be impossible for someone who doesn’t know the terminology; they may not understand what the staff is saying to them. So, being able to know the scheme for a place is an essential part of accessibility.

Beyond the scheme, there has to be sufficient space and time to get messages across. That may involve talking (free of interruptions), typing, or signing.

As with the other levels, whether this level is being implemented well really only depends on the person’s self report of whether they felt they could understand the scheme and communicate effectively, not just on whether the staff at the space felt they were providing enough options.

Some design points to consider at this level are:

- agendas, glossaries, other written information exposing the scheme (Agendas are also called “visual schedules” in the autism world.)

- name tags

- signage – explaining the purpose of spaces

- languages available to communicate in

- the kinds of communication available – In particular the choices should include those that don’t have the instant feedback factor, like email. This lets people use the space, even when their communication is subject to anxiety or isn’t reliable.

- the commitment to the accuracy of what is said – In particular, if an agenda is posted, then not adhered to, it isn’t helping the space be more accessible.

The kinds of people who may find communication accessibility important include anyone who has identified communication problems, and anyone who doesn’t share information in ongoing informal encounters, and needs it to be more intentional or structured.

Agency – autonomy

At the agency/autonomy level, the question is about having control over one’s experience. A space is accessible on this level when the person can participate and achieve the results they want equally to others. This doesn’t have much to do with the buildings; it’s about the program and power dynamics.

Some places that excel at this kind of accessibility are libraries and grocery stores; there is an assumption that the user/customer is in charge of their time, and may come and go at will, take as long as they need to, and get anything they want. No one is supposed to second guess whether the person should get the item they picked out. The user participates in the outcome – not completely controlling or owning the place, but participating autonomously. So, it is easy to think about autonomy-related accessibility by comparing some space in question to the experience of grocery stores or libraries.

Some design points to consider are:

- Personal boundaries in terms of physical distance.

- A time organization scheme that does not rely on time-pressured responses. To make it very accessible, there could even be no questions at all, because questions are interpersonal demands for information on the asker’s schedule. An alternative would be to provide a way to give information without the expectation of that being instantaneous.

- Rules of order. Particularly in spaces where decisions are made, establishing and actually following through on turn taking and other rules of order allows people to participate more equally. When these are forgotten, those with higher social rank control the communication and the disabled lose out.

- Interaction badges

- Representation. In spaces where one is a minority and is outnumbered by people with a different power level or agenda, the minority person can lose autonomy simply from the feeling of isolation. Therefore it is important that minorities be represented multiply, not singly, and further that they can interact on their terms and not be each isolated from their peers. Public spaces designed for the majority already provide this advantage to the majority, so the technique of opening the space for others of a kind to work together helps make the space accessible to the minority as well.

When the autonomy dimension is right, the person has the psychic space to maintain their own perspective. Psychic space is a product of time, physical space, comfort (coming from the other levels of accessibility), and the reflection of similar other people (one own kind). There’s a continuum from feeling very grounded, all the way down to feeling completely cut off from oneself. In the extreme, a space that is very inaccessible has elements in common with being in an abusive relationship, because perspective is lost in a similar way: the victim usually loses their sense of self worth and is gradually weakened by the other person. For some vulnerable people, just going into an everyday inaccessible public space causes a loss of perspective and self worth, and perhaps they can’t identify what specifically is not working because they are cut off from their full reasoning power. The reason it happens is because the kind of alienating things listed above are happening (such as violating boundaries, lack of rules of order, and isolation). In accessible spaces where those elements are improved, people feel whole and not sidelined, and not lost or confused by interpersonal power dynamics.

To achieve accessibility for a particular kind of person, it follows that that kind of person would need to make decisions about the space; it can’t really be done “for” a group. Autistic people would need to be active in creating autistic-accessible spaces, for example; and the same for blind and deaf people, and so on. When something is done “for us”, not matter how good the intention is, the leadership perspective is different, and that colors all the interactions and limits the possible outcomes to those pre-conceived by those with more power.

Practical examples

In these practical examples, I will make some evaluations of how well some spaces do on deep accessibility, and how they could do better. I’m mainly including comments on the architecture, communication, and agency levels. The sensory level is becoming more understood, and the kinds of strategies needed apply pretty equally to all buildings: removal of fluorescent lights, protection from noise and the other things listed above. Almost all public buildings could easily become more accessible on the sensory level.

1. web sites

There is some theory out there on “cognitive accessibility” of web sites. This centers on what I’m calling the communication level. In general, a web site is accessible when its organization is transparent, discoverable, and consistent.

Some web sites migrate over time to become a messy thing that you can’t navigate around, you lose visual cues on how you got to a place and can’t go back, or can’t remember how to get to a place again. By contrast, an accessible site has a scheme (a knowledge tree) that gives the information about “this is how you use this site”; that scheme becomes apparent and the person can apply it and use the terms of the scheme to effectively use the site.

Factors that improve accessibility include menus that expose the breakdown of available information, only having 1 menu (instead of 3-4 like on many web sites), and separating out navigation from content. A site can have a totally novel way of using it, but as long as that scheme is discoverable and consistent, users will understand it.

A common mistake in web accessibility is trying to guess how people think and tailoring it the person you expect, without accounting for a range of people with different ways of thinking. As an example, suppose a government agency or company has many parts, and users typically do not know how the organization is structured. There are two opposite approaches to this: (a) mirror the site to the actual organizational structure, and show users what that structure is; or (b) build the site around the anticipated needs of the users, hiding the complexity of the actual organization, and adding a lot of links between in the site. The first way is older, and tends to be more accessible: no matter how the user thinks, they have the opportunity to learn how the organization actually works. The second way tries to make the site “smart” about anticipating what a user intends, but it only works for users who think in the expected way. The inaccessibility is compounded when they react to observed misunderstandings by adding multiple ways to do things, or multiple vocabulary terms for the same thing.

The IRS recently changed their front page. It used to act as a table of contents showing how the site was laid out (more accessible). Now it has 5 separate menu areas with a total of 114 links, that are a jumble of broad categories and details, with no discernible reason why one menu is different from another. It has unhelpful titles like “information for” and “resources”, “get important info”, and “for same sex couples and certain domestic partners” – all of that mixed in with detailed links like “File your form 2290”. Now (less accessible) I would have to stop and re-frame my target information into what kind of user I think they think I am; their actual information structure is no longer exposed.

(Also important but not covered here are web accessibility issues having to do with screen readers.)

2. grocery/retail stores

The organizational scheme of a retail store is important, just like for web sites. Wal-Mart is a store that excels in communication accessibility. (Although it has other issues, I’m just commenting on this one aspect.) Unlike some other big box stores, their labeling is very factual and the system of using the store is very consistent and untroubled by membership cards and other complexities. Big bold letters say “Jeans $26” or “Returns” and they omit the socially complex style of advertising and wording that some other stores use. I suspect the fact that it is accessible is related to the idea of “Wal-Mart Americans” – which may be insulting, but the truth behind the insult is that the population with disabilities probably finds that place more accessible.

A lot of stores have poor accessibility when it comes to the product organizing aspect of the knowledge tree which manifests as the departments or aisles. For example, those of us who think of bread, bagels and tortillas as similar are dismayed to find them spread out in sections such as factory bread, separate from store-baked bread, separate from ethnic foods, and so on. Not everyone’s taxonomy of the items is the same, so it would help to have it exposed more clearly, and also be divided out based on something more objective than whether it is “ethnic” or not.

3. service businesses

Unlike retail stores, a service business like a mechanic requires the customer to interact, so the accessibility issues can be more important. Most people have felt alienated by a mechanic or someone in some service business, or were the victim of aggressive up-selling – not just so-called people with disabilities. That is partly the intent of those kind of businesses. Title loan businesses and perhaps phone stores are a couple examples of businesses that don’t even require a retail store front, but they set up as a retail establishment in order to lure people and then intentionally manipulate them. They can exploit the customer’s ignorance about the scheme (the types of phone service, for example) and isolate them.

So what would accessibility look like? On the communication level, the business model would be exposed, so you could understand what they are being paid, and what you are getting for it – for example if they are getting a commission or if they are paid a salary, and by whom. It would have the feel of the Wal-Mart “Jeans $26” sign – absolute facts about the available service without complications. One could do comparison shopping.

At the agency level, accessibility for service businesses would feel like 2 equal business-people striking a deal, or as if the customer was a supervisor who is hiring the vendor to perform the service. There would be time and space to decide. The contract would be written and honored.

4. schools

The traditional architecture of schools expresses some of the values behind the curriculum – that students are to be herded and normalized, that classrooms are separate power domains of mostly autonomous teachers (not working together), and that escape is futile. So in that sense they aren’t meant to be particularly accessible. One could imagine a non-compulsory school that does not need to have equal-sized classes of same-aged students, and this could have a very different architecture supporting those values. For example it might not be so blocklike with so many similar closed off rooms. It might be more than one building along a street with outdoor areas shared with residence and retail and parks, rather than a fenced-in campus. Any of the other possibilities could be more accessible, if that were the goal.

At the level of agency, schools are of course highly controlling. For most students though, there is leeway – room for negotiation and time to be yourself. For students in special-ed classes, there can be less. The recent effort in schools to explicitly cater to a wider range of disabilities seems to have backfired in some cases. For example, if an autistic type of child is under the radar (largely left alone), the school could be more accessible for that independently minded student. But when he gets labeled and “given” special services, the teachers may then get more invasive and reduce the amount of privacy he has. I’ve seen teachers seize and search students’ backpacks just because they have a disability label, not for any suspected transgression. Knowing that your life is under continuous scrutiny makes the whole place threatening and much less accessible than being left to fall through the cracks.

5. doctor’s office

There are a huge number of idioms used by doctors, that people may be unfamiliar with. Every time I go to a doctor, I don’t get what they are saying and have to ask a couple times. Someone who is more embarrassed about exposing their ignorance than I am might not be as persistent and would end up not being helped. Like, what is “dropping” pants? (underwear too?) Do they really re-fill the same bottle when you get a “refill”? How much is a “lot” of pain? More complete and objective speech would make it more accessible on the communication level.

There’s a common complaint about doctors being condescending and just telling patients what to do, taking power over the patient’s body. My sense is this is worse when the patient appears weak or vulnerable, or has a disability. Improving accessibility at the level of agency would involve making sure the same level of decision making about treatment is given to all patients, with the same options provided.

6. autism services

I’m now moving into autism-specific examples, because the very things that are intended to “serve” autistic people should be the places that are most accessible. Someone may want to access some help, but doesn’t want to go through a gatekeeper who may demand language they don’t have at that time, may invade privacy, or who works in a loud and confusing place. So the very people who could potentially help with access issues can themselves be an accessibility problem. For myself, I could use some autism-related services because I experience autism-related problems in life (mainly employment issues, stress and anxiety, sensitivity) but I don’t access anything because I don’t trust the people in charge of those things, they’re not my kind of people, and they don’t seem to offer anything that makes sense. As a case in point, one of the people who diagnosed me made a marketing call a month afterward to try to get me to take drugs, without having done any medical testing or evaluation of any kind – which is the kind of thing that leads to having no trust of that system.

At the communication level, there are a number of issues with the current system:

- Acronyms and bureaucratic speech can inhibit the transfer of meaning. Professionals use words from abstract psychological theory or words from legal or institutional sources, which may not map to how the client understands – like behavioral health, behavior intervention plan, depression, ego, disorder, and perseveration, to name a few. The person in question may be sad because she can’t pursue an interest, but the helper may say her “depression” is related to a “perseveration” and ask about “hobbies”. The gaps between natural speech and terminology can be an accessibility barrier.

- Politically motivated terminology like person-first language builds shame around saying what one actually means, making it not only impossible to speak, but to even collect ones thoughts.

- The language of being “broken” of having “deficiencies” sets up a hostile environment where a person would not want to go for help.

- Some professionals adopt an almost sarcastic hyper-inflected tone (like baby talk), which can be highly repulsive.

- Speech topics can create a barrier to autistic clients – for example small talk or other culturally scripted speech.

At the agency level, it appears one of the main problems inhibiting the success of any autism services is the gatekeeper – a non-autistic hierarchy of people who determine what services are available and to whom they may be given. The concept of what a client needs in the first place is, from what I’ve seen, completely in the domain of the provider, and it is skewed towards drugs and behavior control when those are usually not the main services that clients would seek. At its worst I’ve seen it involve forcing “services” on someone (“we can’t have her wandering the streets, so she has to go to day-hab”).

It may be a stretch to call this an accessibility problem, but it appears that there is an army of well-meaning people trying to make a living “helping”, but yet they don’t seem to be available to the people needing help. Even when people experience needs as very specific immediate things (I need to get to 4th and Central, or I need an alarm clock, or I need to find my key which I keep losing), the gatekeepers say we don’t offer that – we offer help, except for in all the ways you need it!

And hardly any of the people doing autism services seem to know how to talk to autistic people under stress; they demand language on their schedule, interrupt, and escalate the volume. The more credentials someone has, the worse they seem to be at communicating with me, in my experience. When there are no rules of order, it is not possible for us to participate in conversations regarding our own services.

So what would accessible autism services look like? This is a variant on the question I’ve been asking a lot with no great answer: what is the proper public policy action to take concerning autism? What should be we doing instead of having a panic over an “epidemic”, or pursuing insurance reform to flow more money to behavioral training?

A quick answer is that the entire autism services framework could be morphed into more of a “resource center” concept, where it works more like a library of offerings, with these accessibility features:

- At the sensory level, the place where the help is rendered should be highly controlled for noise, light, air quality, and texture issues. People can tolerate some sensory badness for a lot of time, or a lot of badness for a little time, but to the extent that the client’s energy is invested in protecting against sensory onslaught, that energy isn’t available for the purpose of the visit.

- Resources could include things that autistic people often like and want, like devices to manage sound and light (ear protection, Irlen lenses), weighted blankets, stim toys, and other physical resources, as well as tablet computers with relevant apps and other communication devices. Visitors could try or borrow all these things and determine what works for them.

- The resources available would be built up over time based on what works, according to the clients.

- The people using the space could build a community with each other, instead of using the medical model where one assumes that the “patient’s” needs for confidentiality should isolate her from all other “patents.” That would provide for some representation of viewpoints, that would make it possible to maintain ones perspective in the space.

- The physical space could be open to just be in as a hang-out spot; that’s a “service” that is usually not available anywhere.

- The staff of the service place would include autistic people.

- The architecture of the space would be informed by the values inherent in these points. It might not be like a classroom or an isolating doctor’s office, but architecturally more like a library.

- Professionals would be available for talk therapy and advice, but not necessarily in the role of case management; you wouldn’t have to sign up to be under someone’s direction.

- When it comes to people who apparently cannot make decisions in this model, for whom it seems that they need more direction, I still think the model works, but the services are more comprehensive. This includes children or others who don’t have the knowledge base, language, cognitive function, or whatever (yet), to make typical adult choices. For some, the resources they come in for are going to be more intensive, up to and including 24 hour care or supervised housing.

- At the level of language, the words would be “this is a place where you can…” The costs or availability of services would be listed out (not in secret), so it is clear what is possible and what is not.

- The resource schema would be clearly defined. Things that are borrowable or just for looking, or things that are free would be distinguished. The organizational scheme would be exposed.

- The way a visitor to the space gets help (whether in physical space, calling or a web site) is similar to a library: you can ask for advice, you don’t have to take it, and you can ask as many times as you need to; then when you need to “check out” you present the resources you want, and they are evaluated based on a transparent system. In the end you get permission or not, or there may be a cost. The limitation on services could be done in a simple way like a total annual amount based on a disability level (not by being so-called “medically necessary”). The model has to work within real budget limits, so not everything will be free and unlimited.

With all these accessibility points in place, the availability is improved and the things that people do on account of disability would shift. The medical model would give way to this “library model”. People would be more creative, efficient, and targeted in designing what service they really need. Things that are out of scope of the current system would be possible.

7. disability professionals’ spaces

There are spaces I’ve been in, which are mainly for disability professionals and parents of disabled children, such as conferences, the events of the Autism Society, and an advocacy training program called Partners in Policymaking. When I tell other autistic people about being in those spaces, they intuitively get that it’s like going into the lion’s den, and even say that I’m brave for even trying it. Yet the professionals never seem to be able to understand that. One doctor insultingly asked if I served on a board in order to get personal support, assuming that other board members are serving their community but and I’m only there for selfish reasons.

Here’s an example to illustrate the hardship in being in spaces like that. A conference speaker announced with a great smile the conclusion of her research, which is that autistic people “don’t know how to learn” – and a hundred people in the audience nodded in agreement or took notes. (This actually happened.) To promote an absurd scientific falsehood like that into their group social truth is a hostile act, quite as if she had turned directly to me and said “you there in the second row, you are a pathetic turd”, and then everyone in the room nodded in agreement. While those spaces feel hostile, people are being outwardly courteous, and that makes it difficult to spot the source of the problem.

In one case where I ran out of spoons and couldn’t continue being in the space, the reasons ranged from sensory (the lights, noise and artificiality of a hotel conference room), to the communication (person-first and other language implying brokenness and disease, the ideological constrictions, and the marathon length of highly repetitive speeches), to the agency level (it felt like being in school). When I stopped I was told they could have provided an accommodation. In terms of the graphic at the top of this paper, that would move me from the excluded category to the accommodated category. I thought it was interesting to consider that idea, and wondered if I would want to participate in something that wasn’t accessible, but be there in some accommodated way? Would the accommodation give me a privilege or lower the expectations on me? (“Everyone has to sit through the speeches, except her.”) I never answered that question because I couldn’t think of what purpose staying on would serve.

When I served as a board member of the local Autism Society, the inaccessibility was similar to the above example but with wider consequences. Almost every problem mentioned in this paper would be happening at the same time, and I’d be reduced to a shivering bundle of nerves. When I asked for changes, even simple ones like not interrupting or not meeting in a loud coffee shop, some other board members would actually fight back. They were willing to “accommodate” (meaning have the autistic board members skip meetings, not have any real responsibility, and generally play a second-tier role) but they were unwilling to include by making it accessible – possible for me to be there as a full participating member.

That ultimately means the Autism Society could not or would not include autistic voices; maintaining the power differential appears to be a core part of their group identity. I suspect that autism professional’s spaces will be the last places to ever become accessible.

8. adaptive recreational programs

There’s a concept of “adaptive” programs which seems to mean “changed so that disabled people can do them”, and it is often applied to sports but can be applied to any activity like yoga classes or acting or outings. When people think of “adaptive”, I don’t think it is the same as what I’m calling “accessible”, but there is some overlap. In my experience, I have not been able to do most of the socially complex things out there (dance classes, sports teams, etc) but I have participated in some adapted programs. One dance program I did was disability-inclusive and worked fairly well. Another drama program that was specifically for autistic people left me feeling extra-disabled. The difference between the two programs is instructive of what constitutes the agency level of accessibility. In the dance program, the whole cast was treated the same (same rules, expectations, etc), but some of the disabled ones had assistants. The hierarchy was: director – dancer – assistant. In the drama program, there was a majority of non-disabled people who all had teachers-pet status – they got to co-lead the program, while the rest of us were more like the children being led. The hierarchy there was: director – aide – disabled actor. So there were people helping the disabled people in both cases, but the power arrangement was totally different.

Another big difference was the creativity and feedback. In the dance program, each dancer was expected to choreograph some of the show, and it was acceptable to express opinions and make suggestions to the director. But in the drama program, things were arranged so that no feedback could ever occur, and “creativity” was channeled into a narrow pre-determined sequence of choices.

When I was in the clamped-down situation, it was difficult to think about what made it feel disturbing. Even though other autistic people were around me, we were isolated from each other because the director would always intersperse the normal people who would take more leadership. I could sense fear whenever “too many” autistic people were together unsupervised, and we were on the verge of bouncing energy off each other and coming up with something from our way of thinking; before that could happen, the normal people would quickly act to separate the critical mass.

My hopes for these kinds of adaptive programs are:

- Deal with sensory overload with quiet spaces and deal with lighting and noise issues everywhere.

- Use the word “peer” correctly; in a disability context, it means someone similar, like an autistic person to another autistic person. It’s often sloppily used to indicate a superior (non-disabled) person of the same age.

- Make the social arrangement open. For example, if the program is open to literally everyone regardless of disability, then acceptance should not take disability into account. If it is only open to people in a certain disability class (which is fine), make that explicit. If you want it to have half disabled and half non-disabled participants, then make it explicit who was admitted into each class. But don’t pretend everyone is equal if you actually brought in one class of participants as “role models”. (And ask yourself why. If you really want the inferior students to mimic the normal role models, it’s a mean spirited program to begin with.)

- Give up on the goal of having the appearance of a normal experience. For example, adaptive “rock climbing” for someone who doesn’t have arm strength and cannot actually climb might really be an experience of rappelling or of swinging on ropes. So call it that; don’t use your sadness that the person will never climb as a reason to just pretend they are having the same experience. When the experience becomes coated in fake words, it is a communication accessibility issue.

9. retreats

Autreat is an autistic-run annual conference and retreat. Partly because it is held in college campuses, it takes a lot of work to make it accessible. The success of that in my experience is mixed, and that is due partly to the limitations of the physical space and partly to the limitations of the ability of the planners to organize and orchestrate a complex program in a new space.

I’m in the process of building a retreat center – as of this writing, working on the access road and drilling a well, so it is not very far along yet. Since one of the main purposes of the place is to be accessible to autistic people, I’m thinking both of this place and of autreat when considering deep accessibility for retreat settings.

At the level of movement, I’ve planned for the retreat center to be quite compact and have no steps, so there don’t have to be “extra” ramps or routes for people who roll. That way, everyone can access the same routes.

At the sensory level, I think the retreat center will excel because it is remote, quiet, and will have no excess lights or machines or other noise sources. Lighting will be LEDs. Mechanical noises will be limited to refrigerators.

At the architecture level, there’s very simple scheme. A defined park in the middle is surrounded by buildings, and further surrounded by a single loop road, so it is easy to get oriented. Each house will have a single main room with bedrooms and a kitchen on the sides, and as the house is rented to the group as a whole, there should be no ambiguity about where it is OK to go and where to find everything. The concentric circle pattern “says” to people, come to the center to be closer to people and go farther from the center to be alone.

The higher levels of accessibility are not in practice yet at the retreat center, so I’ll talk about that in relation to autreat.

At the communication level, autreat has the potential to have a space/time organization scheme that makes it possible for everyone to use the space (and time) equally. There should be a schedule of time slots with the basic expectation that you do one thing per slot; some of them are pre-programmed by the planners and some are filled by public negotiation (open invitation) and some by private negotiation. Then there needs to be a reliable and centralized way to do the negotiation and decide what to do in each slot, such as a bulletin board with voting-stickers or the rule “whoever schedules a room first gets it”, or some system like that. I think that if the system is not adhered to, and the information flow relies on word of mouth or other means, then some people will be in confusion a lot of the time, and the communications won’t be accessible. It is better to be consistent and always stick with the scheme. For people who like to have a set plan for a day, they can work the negotiation system and have it all clearly written.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end! I hope you will let me know your thoughts on deep accessibility in the spaces you go to.

“For some vulnerable people, just going into an everyday inaccessible public space causes a loss of perspective and self worth, and perhaps they can’t identify what specifically is not working because they are cut off from their full reasoning power. The reason it happens is because the kind of alienating things listed above are happening (such as violating boundaries, lack of rules of order, and isolation).”

Wow–this is exactly what happens to me. That’s a great insight!

“Politically motivated terminology like person-first language builds shame around saying what one actually means, making it not only impossible to speak, but to even collect ones thoughts.”

What does this mean?

“One doctor insultingly asked if I served on a board in order to get personal support, assuming that other board members are serving their community but and I’m only there for selfish reasons.”

This is EXACTLY the problem I have with the term “self-advocate.”

This is absolutely brilliant. Thank you for sharing this. i gotta say, i got a bit teary reading some of this, particularly the way these things were really thought out, brain-wise, heart-wise, community-wise. Really lovely, useful, clear, expansive. Definitely passing this along.

[…] https://ianology.wordpress.com/2013/09/06/deep-accessibility/#comment-296 […]

Reblogged this on jonesyj08.

Hello,

I love your article. Do you have a text description of the figure for blind people? I want to post and share on my Facebook but need to add text description to make it accessible for blind people. Thanks!

E. Hibbard

Hello, thanks for this article. I’ve been studying universal design in relation to permaculture design, and your clear logic has made many things much clearer to me.

[…] Access is not a simple question. For me, it’s not just about “can I show up?” in a space. Some of access for me is about shifting my framework for how I’m going to play. […]

[…] For more discussion on deep accessibility, see this paper. […]

[…] For a deeper understanding of all that accessibility can encompass, try reading resources such as this post on Deep Accessibility. […]

[…] Starlys. (2013). Deep Accessibility. Retrieved from https://ianology.wordpress.com/2013/09/06/deep-accessibility/ […]

I’m an (autistic) developmental pediatrician. Could I have permission to use your “Deep accessibility” image for a talk I am giving to the American Academy of Pediatrics on disability bias? I want to demonstrate the social model of disability and how communities choose who they expect, ,accommodate and exclude.

Of course, and thanks for asking!

I love this piece you’ve written and I think the graphic at the top is super helpful. I would like to include it in a presentation I am offering as well as a blog post I am writing – I will provide attribution and link back to your piece in both instances. Could I have your permission to use your graphic in that way?

Sure that would be fine!

Hi! I have read your book twise “a fieldguide to earthlings” with excitement and fascination. Some of the patterns you mention I realized growing up but I had a more intuitive feeling about them rather than beeing able to verbalize them. I would love to participate in the Oacle Cliff project if it is still on. Where can I find more information about it? Also, I think I have the ability to see auras aswell, I always thought I was beeing manipulative or reading through people. Looking forward to hear from you. Thanks.

Kaiwan, Please email me at star@divergentlabs.org – would love to hear more and have you participate with Ocate Cliffs.